Conceptualizing a Performance

My creativity is inherent to my being, and I can’t recall it not being a present energy in my life. My first drawing ever (I kid you not) was a diptych; on one side of the paper was an observation drawing of the underside of our ironing board (which I vividly remember gazing up at it from my spot on the floor), and the other side of the paper contained a rendering of an ostrich because they were my favorite animal. I was 4. I have spent my entire life on a journey with this (sometimes deafening, sometimes elusive) artistic voice— trying to find it, nurture it, fight it, and love it. I spent 7 years in art school, and the 7 since graduating teaching at art schools with no plans to stop. The decision I made to pursue training in making and feeling was the single best decision I have ever made in my life. I hope to be able to share with you some ways in which I make. Specifically, in how I make a pole performance so that you can glean some ideas on how to construct one yourself. Words will always fail to lend meaning or description to my process, which is often times messy and non-linear, but nonetheless always fulfilling. This is the closest thing I’ve come up with:

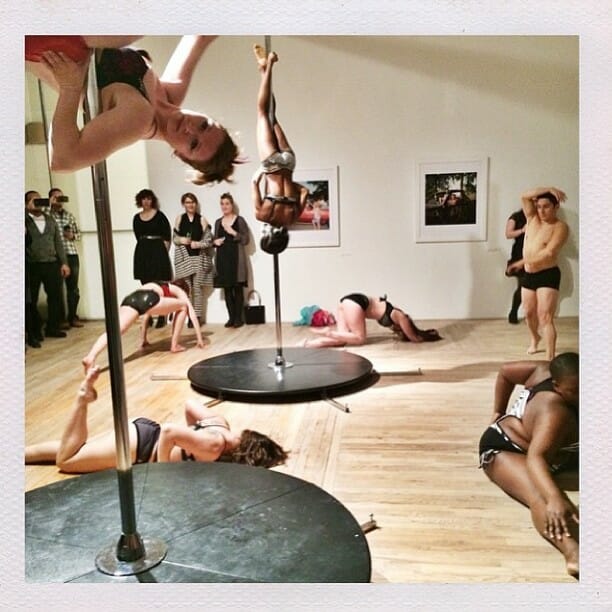

*Disclaimer: I personally do not operate my pole practice from the lens of physical athleticism, but rather, I draw from performance art, sound, theater and video. I subscribe to the Artaundian “athlete of the heart” school of thought. The following material may not lead you to a win at your next competition. I do not aim to formulate a medal winning recipe. Rather, I hope to suggest to you ways in which you can experience a journey toward something you are proud of.

_________

Conceptualizing a Performance

1. Artistic Voice: Listen to it. Mine has a bull horn and fireworks. Yours might be a whisper. Your artistic voice is the thing that tells you to make. Do not ignore this voice.

2. Inspiration: There is no wrong way to start creating a pole piece. Think long and hard about what you draw energy from. What gives you feelings? What inspires you? My starting point is always sound. I spend a lot of my time experiencing the aural languages that composers use to create meaning, and it speaks to me on a level that spoken language and image language never has. Inspiration can be drawn from many sources, ranging from general broad ideas, to tiny detailed experiences. Are you inspired by theatre? The color red? Blades of grass? Sadness? Your pet dog? Social issues? The possibilities/limits of your own body? Find the thing that makes your heart beat fast and investigate it.

3. Starting point and Idea: Story, Mood, Form.

When conceptualize a routine, the potential starting points are endless. I’d like to discuss three primary beginnings that I have seen surface in my creative process throughout the years. Your concept can be separate from these ideas, or a merge of them.

-Story- This may be the most straightforward starting point. Do you recall a memory that you would like to share with others? Have you created a fictional character? Is the narrative linear (beginning, middle, end) or meandering, or some other order? Are there characters? Who are they?

-Mood- Moods are a little bit looser than stories. In my opinion, starting with a mood pulls you out of the realm of story, but not quite into the realm of form. Sometimes constructing an entire story is too much, so its important to be able to identify the times in which story needs to be broken down into its essence. Moods are mental or emotional states. Perhaps you don’t necessarily have a character, but you know you want to convey confidence. In this case, confidence is your starting point. Your mood can also be a singular state, a dualistic one or something else completely!

-Form- Starting with form means placing emphasis on developing or displaying craft and physical execution. Many people like to start from the desire to display physical prowess, and this assertion can make for a very “wait, she just did what?!” performance.

4. Shape: Now that you’ve figured out some inspiration and a starting point, you have to start creating shapes. Your shapes should fit your idea. Even if you have the cleanest, most perfect Titanic in the world, if it doesn’t work with your idea, it needs to be left out of your piece. I mean to suggest that your shapes and combos should informed by your concept, not the Trick Combo Du Jour on Instagram. Pro Tip: Play with shapes with alternative head/hand/foot positioning. Your Jade Split can go from sex pot to agony with a simple modification of head placement from an extension to a tuck. When it comes to shape, the most important question to ask yourself is whether or not you care if your tricks are “correctly executed” or evocative. There is no wrong answer to this question.

5. Costume: One of the hardest things I’ve ever had to come to terms with is the fact that rhinestones don’t belong on every pole costume. I am serious. This was hard for me. The thing you wear on stage should reflect or exist in conversation with the construction of your piece as a whole. This may sound like a no brainer, but one of the most troubling aspects of pole showcases and competitions I have seen is costuming. The sports bra is for the studio, not the stage. Rhinestones need to stay at home sometimes. Other times, they need to gush from your very pores. Hair and makeup is part of your costume. Kim K/Victorias Secret flowiness is not appropriate for that piece you made about sadness even though your sexy hair game is really on point. Your costume needs its own language. Let it speak.

- Body Diversity, Positivity, and Acceptance in Pole (OR “Skinny Bitch’s Guide To Not Being An Accidental Jerk To People Larger Than You”) - April 7, 2015

- Conceptualizing a Performance - February 10, 2015

- Pole as Activism - December 16, 2014