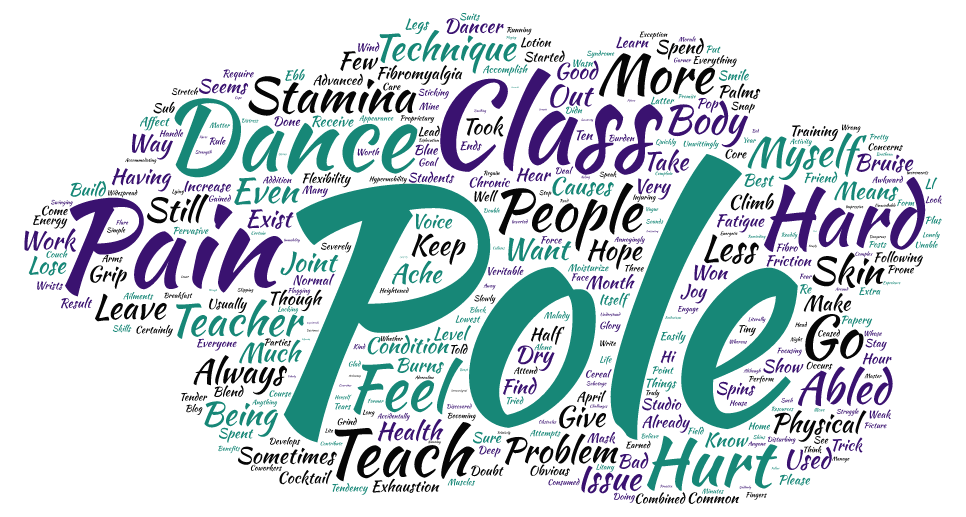

I asked this a few weeks ago via social media and many people had some…

Pole Dancing With Health Problems

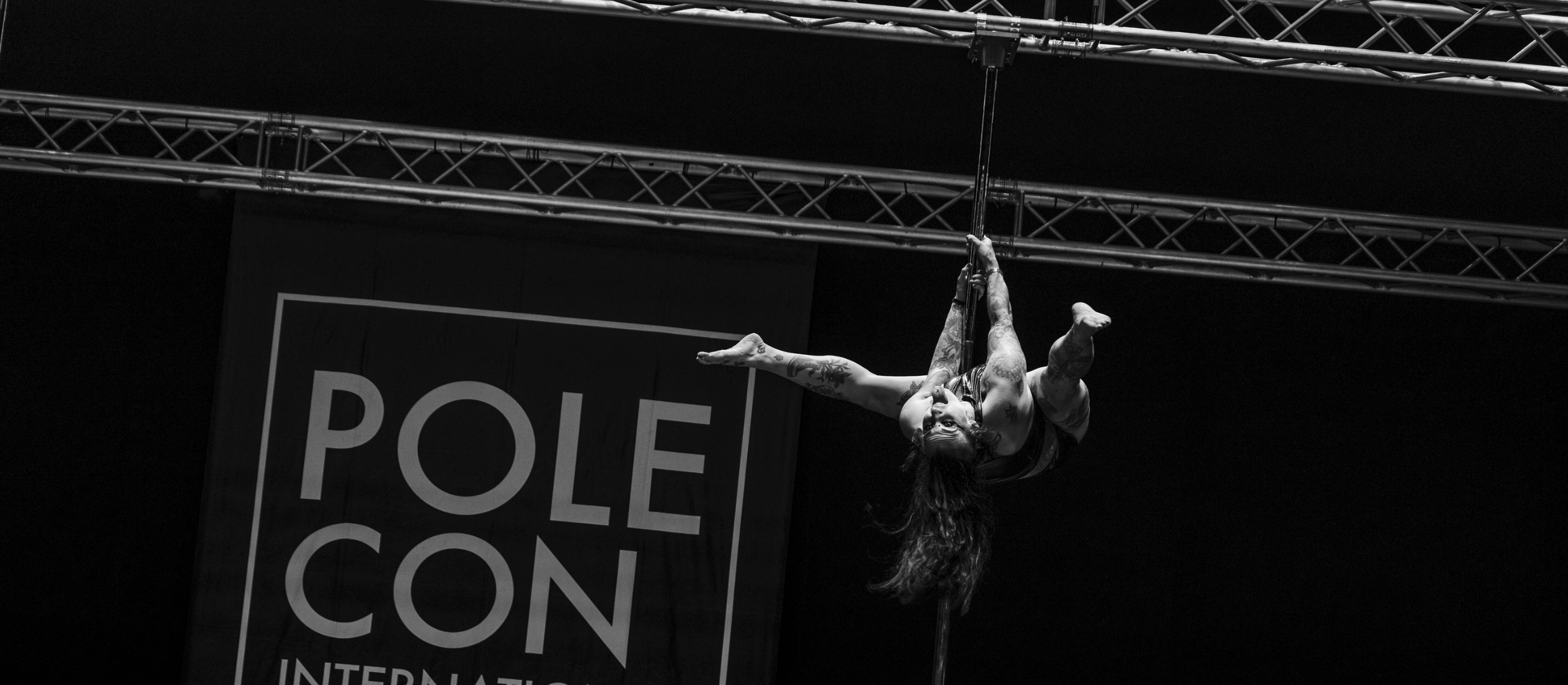

Pole dancing is hard for everyone. But it’s hard for me in ways that other people don’t always understand. It might not be obvious that I’m less-abled, that my body has a tendency to sabotage itself, because my smile and enthusiasm for pole dance unwittingly mask an existence of hurt and exhaustion.

Hi, I’m April and I’m a dancer with Health Problems.

It seems to me that most people with health issues don’t have just one, but a veritable cocktail of ailments (Cocktailment? Sure, let’s go with that.) and I doubt mine is a proprietary blend. The following is an overview at how my physical concerns affect my pole training and teaching:

- Dermatological problems — These result in having papery-dry skin that tears easily and has no grip. It took me six months of awkward, frustrating attempts to climb before I accidentally discovered that I am the exception to the “NO body lotion!” rule. If I don’t moisturize my legs the night before class, I will have no hope of sticking to the pole. My severely dry skin also readily develops friction burns.

- Joint problems — Hypermobility, or being “double-jointed,” can be useful for the pole techniques that require flexibility, but it also leaves me prone to dislocation. Even when my joints stay where they should, they still pop, grind, and snap — almost like some disturbing breakfast cereal.

- Fibromyalgia — This annoyingly vague malady causes me to have heightened sensitivity in my skin and widespread aching in my muscles. Even though I’ve conditioned my skin — acclimating it to the pain of pole techniques — the deep ache of bruising still occurs. I don’t always get the glory of a well-earned pole bruise to show off my hard work because sometimes the black and blue doesn’t show up, but the pain always makes an appearance. It doesn’t matter how many climbs I’ve done, they leave my shins tender for days. In addition to the common pole condition of calluses on the palms, when I spend time focusing on spins I can come away with bruised palms and friction burned wrists. Fibromyalgia is not just about everything causing extra pain, it’s also about the pervasive hurt leaving you weak. When I’m having a fibro-flare, I can perform very few techniques before my fingers lose their grip, my arms give out, and my core won’t engage — a dangerous combination when doing anything inverted.

- Chronic fatigue syndrome — This condition causes me to lose stamina quickly and regain it slowly. Sometimes, it can be hard to know where the fibromyalgia ends and the chronic fatigue beings. The pain of the former can lead to the exhaustion of the latter, though not always; there will be weeks when I’m pain-lite, but consumed by fatigue to the point of immobility.

Before I started teaching, I would attend one class a week. Often, I would wind up skipping one week a month when I was at my lowest ebb for fear of injuring myself on the more advanced techniques. After becoming a teacher, I don’t feel like I can keep asking the other teachers to sub for me because, while my coworkers are very kind and accommodating, I don’t want to be a burden to them. Sometimes to my detriment, I force myself to go to every class, usually running on adrenaline and hope.

It’s lonely feeling like the only one who can’t physically keep up, the one who is already flagging half-way through the class. I look at the other teachers and students and find myself lacking, not because my technique is less advanced, but because I will never have the stamina to keep up. One of the teachers at my studio usually has six or more classes (plus parties) a week. I teach one lower-level pole class and one stretch class a week and even that can be too much for my body to handle; I might spend the following day (or two) lying on the couch aching and unable to move. It’s not a pretty picture.

There’s a voice in my head that says: ‘You should be able to do this, just go to more classes and you’ll build your stamina.’ But that voice is wrong. My stamina increases in such tiny increments that it took a year-and-a-half to build up to two classes a week. Some weeks that is still a struggle to accomplish.

My own pole training has almost ceased to exist since I started teaching; I hear that this is a common problem because time that had been spent taking classes is suddenly being used to teach them. However, since I only teach two classes a week, time is not the issue so much as it is energy. Two hours a week and I’ve used up most of my physical activity resources. If I’m having a good week and have the energy to practice at home, I still only have stamina for ten-to-fifteen minutes a day. This means that I can spend that time spinning or conditioning or working on a trick, but not all three.

If it hurts so much, why not just stop pole dancing? It’s certainly what some people do. I have a friend who also has a litany of health issues and tried pole dancing for a few weeks before deciding it wasn’t for her. She told me that she’d already spent so long in pain she didn’t want to deal with any more of it. I’m glad she knows what suits her body best and is able to take care of herself. However, that’s not what’s best for me. I will hurt whether or not I pole dance, and the joy I receive from pole dancing makes the pain worth it. It gives meaning to the pain when so much of my pain is unpredictable and unavoidable.

Pole dancing can contribute to my physical distress; of course, so does everything else in my life, and the benefits I receive from pole dancing more than make up for the hurt. The strength I’ve gained, the skills I’ve learned, the friends I’ve made — all these things combined with the simple joy of swinging around on a pole form an experience that I won’t give up.

I read blog posts about people who are accomplishing amazing things and whose goal is to master a certain complex trick or increase their already impressive flexibility and I feel bad about myself because my goal is simply to get to class. When I manage to go to class and it seems like all I see from my fellow teachers and students is how hard they’re able to work in the studio, I think about how hard it was just to get out of bed. I have to keep reminding myself that I literally cannot compete with anyone else; they are ‘normal’ people and I am ‘other.’

All this being said, I do have good days, although a good day means I can feel successful in a one-hour class, whereas a bad day means I don’t leave the house. There are times when I am relatively energetic; this doesn’t put me on a level playing field with normal people, but it’s a morale boost. I take what I can get in life.

I promise I’m not writing this to garner sympathy or to complain (though it certainly sounds like I am). I write this with the hopes of finding the other less-abled and differently-abled dancers. I can’t truly believe that I’m the only one out there, even if it feels like that sometimes. So, my otherly-abled pole-brethren, please speak up. I want to hear your stories. I want to learn about what challenges you face and how you cope with your obstacles. Please, let me know I’m not alone. =)

Image created by Tagul.com

Latest posts by April Rayne (see all)

- Choreographic Devices - July 21, 2017

- Choreography 101: Improv - July 7, 2017

- Quiz Time!: What’s Your Pole Style? - April 21, 2017

This Post Has One Comment

Comments are closed.

As a more voluptuous pole dancer and someone who spent a lifetime not moving, I often feel like I’m not on the same page with the other dancers at my studio. Its so easy to look at someone else and see what they can do and find yourself wanting to be more than you are. I console myself with the thought that we are all on our own journeys. What I may master in one class may take someone else months, and vice versa. Most days that works. On the days that it doesn’t , I give myself permission to come home and cry a little, or collapse on the couch and watch Netflix for hours, or listen to the angsty music of my teen years, but then I get back up and walk back into that studio and try again because in the end everyday that I move is a victory. Don’t give up and don’t be too hard on yourself. Hugs!